What is PeARS Federated?

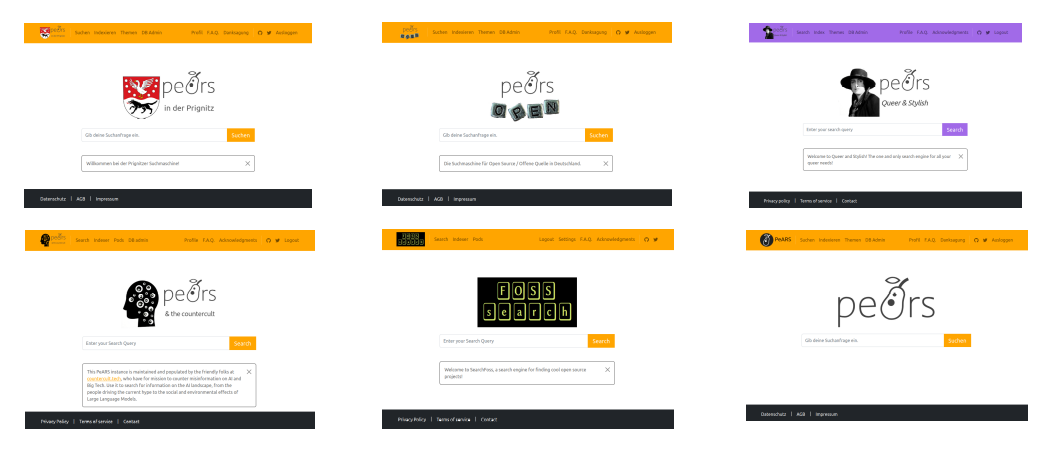

PeARS Federated is the decentralised version of PeARS. You may know the social media platform Mastodon: PeARS Federated is like Mastodon but for Web Search. Every instance of PeARS can be considered a mini search engine for a single topic of interest, which is populated via crowdsourcing. That means that if you sign up for an account, you can contribute to the content of the search index by sharing interesting URLs. This ensures that the index is of particularly high quality, as it has been vetted by human contributors. Taken all together, the PeARS instances cover as many topics as there are contributors. The network is searchable from any instance, ensuring the best possible search coverage for your query.

Status: alpha. If you want to see a preview of the account functionalities, including screenshots, head over to our FAQ page.

General architecture

The PeARS Federated network is a collection of community-run PeARS instances. Each instance is hosted on a separate server by an administrator who is responsible for its maintenance. The admin decides on the scope of the instance (topic, languages, regional restrictions etc).

Aside from the admin, there are two types of users on an instance: those that simply visit and search, as they would do on a ‘classic’ search engine, and those who contribute to the index by suggesting content appropriate for that instance. Contributors must have an account and be logged in to perform actions such as indexing, managing their contributions and accessing statistics on the content of the server.

At the network level, we are working on a Distributed Hash Table (DHT) architecture to let users search all instances from any node they are currently visiting.

How does indexing work?

PeARS implements a collection of NLP tools ranging from classic information retrieval algorithms to state-of-the-art tokenization and lexical similarity pipelines. Documents are converted into three types of representations:

- a sparse vector encoding an unordered set of the tokens contained in the document;

- a collection of entries in a positional index, encoding token sequence information;

- a standard database entry recording basic information such as the URL and title of the document, a short snippet, etc.

These representations are of very different natures, so we additionally keep pointer files that track the location of each document across representations.

To make retrieval more efficient, we bundle topically-related vectors together in so-called ‘pods’. Each pod is thus associated with a) a sparse matrix; b) its own positional index; c) a set of entries in a common database.

To deal with concurrency issues and to ensure users have control over the contributions they make to the index, pods are additionally user-specific. For example, on an instance dedicated to gardening, user Kim might look after a vegetables and a fruit trees pods, while Sandy has their own vegetables pod as well as a soil enrichment pod. This underlying structure is however hidden at search time, and a requester will receive search results from the most relevant pods regardless of their maintainers.

Finally, to ensure instances can be multilingual, pods are associated with a single language but it is possible for a user to have pods in multiple languages under their account. Again, this information is processed in the background at search time.

Roughly speaking, indexing a single document involves the following steps:

- check the URL consents to be indexed (via robots.txt)

- request document, perform language identification, extract raw text

- tokenize the raw text into wordpieces

- generate sparse vector from tokenized document

- compute positions of tokens in document and add them to positional index

- update all pointer files

- update database

- return any errors to the user

The tokenization is performed using a SentencePiece model, pretrained on Wikipedia data. Our partners at Possible Worlds Research are training such models for different languages, which they release here. The reason for using wordpieces rather than words is that we need instances to have one fixed vocabulary per language, and we want that vocabulary to be relatively small in order to maximise compute efficiency. If we indexed words, the vocabulary would grow every time a new word is encountered, and could easily reach over a couple of million tokens per language. As it is, we can limit our vocabulary to 16,000 wordpieces.

How does search work on a single instance?

PeARS ranks documents based on semantics only. That is, the system attempts to find the Web pages most related to the content of the query, regardless of their ‘importance’. We will first look at the search process locally, on a single instance, and then explain how it is possible to search across all instances from any instance.

The first step is of course to encode the query. We treat it as a mini-document and tokenize it as in the indexing process. We then compute its sparse vector representation.

For reasons of efficiency, we do not want to search the entire document collection with every query. We ideally want to restrict ourselves to the subcollection that might be relevant to the user. Fortunately, documents were ordered by topics (the ‘pods’) at indexing stage. So our first step is to identify the k pods that might hold the best results. To do this, we compute in real-time a matrix of pod representations, which are simply the normalized sum of all document vectors on each pod. The reason why this matrix is dynamically computed is that the content of the pods also changes dynamically, as users add pages to the index. We then calculate the similarity of the query to the matrix and retrieve the indices of the k-best elements. Note that queries are usually too short to perform accurate language identification, so we search through all languages by default, but the user can also restrict their search to a particular language by using the appropriate flag.

Then, in each pod, documents are individually scored. Various scores are aggregated, as follows:

-

Token vector similarity: As in the the pod retrieval phase, the similarity between the query vector and the pod matrix is computed, giving a score to each document. The main difference with the similarity computation for pod retrieval is that we are now computing similarity over each word in the query individually (which requires keeping track of the tokens that ‘belong together’ in a word). The reason for doing this is that we want to give preference to URLs that match all or most words in a query, rather than scoring well on URLs that are very related to just one query term. The final score for a document-query pair is the mean of the individual words’ scores.

-

Positional index scores: We retrieve the documents containing any of the words in the query. As in the vector case, we score each word separately and enforce that all wordpieces are present in the document, in the correct sequential order. We then take the sum of the individual word scores.

-

Snippet scores: We give higher rank to the documents that mention the query tokens in the title or snippet of the document.

-

Extended scores: To give as complete results as possible, we also compute an expanded query, which includes tokens similar to the query tokens. These similar tokens are retrieved from a pretrained FastText model, which records embeddings for a 100-million-token subset of Wikipedia. As for the tokenizer, pretrained models for various languages are available from the Possible Worlds Research repository. We compute positional index scores over each word in the extended query individually, but for efficiency reasons, do not enforce the correct sequential order.

We finally take a weighted sum of all computed scores to return the final document ranking. The top fifty documents are displayed to the user.

When searching across several languages, the above process is repeated for each language installed on the instance.

How does search work across the network?

The strength of a decentralised system depends on the ability to interact across instances on the network. At the moment, cross-network search is implemented in a naive way, where each instance maintains a list of all other instances, with their specific language codes and a matrix representation of their pods. At search time, the best instance(s) are selected by comparing the query to all external pods, and an API call is sent to the relevant servers with the user’s query.

This method is however not scaleable, and introduces an additional layer of centralization to the system, as all instances need to be aware of each other. We are currently working on moving this process to a Distributed Hash Table (DHT). In the new setting, each instance obtains a binary signature based on its indexed content, and queries are routed to the best node(s) via the DHT. Document search still happens locally on each node, upon reception of an API call.

Legal considerations

The ability to index Web documents and display result snippets is regulated by laws that differ across countries. The PeARS project has a core team currently based in Europe, so the design decisions we have made are informed by EU legislation. We always check the robots.txt file of a website prior to retrieving the body of a document. We announce ourselves to servers as user agent PeARSbot/0.1 (+https://www.pearsproject.org/). We do not retain copies of crawled documents after their initial processing. Our displayed snippets are extremely short and do not exceed 11 words. We allow users to download URL lists corresponding to the content of individual pods, but none of the other information contained in the index is made shareable.

PeARS - the People's Search Engine

PeARS - the People's Search Engine